Nutrition and aging

by J.E. Anderson and S. Prior1 (4/07)

Quick Facts…

- Eat a variety of foods to stay healthy.

- As we age, it becomes more important that we eat more calcium, fiber, iron, protein and vitamins A, C and folacin.

- To reduce calories select nutrient-dense foods. Enjoy smaller portions of foods high in fat, sugar and sodium.

The Aging Body

Physiological changes occur slowly over time in all body systems. These changes are influenced by life events, illnesses, genetic traits and socioeconomic factors.

Sensory Changes

Sensory changes include a decline in sight and peripheral vision, hearing, smell and taste. The losses are neither total nor rapid, but they do affect nutritional intake and health status.

- Loss of visual acuteness may lead to less activity or a fear of cooking, especially using a stove. Inability to read food prices, nutrition labels or recipes may affect grocery shopping, food preparation and eating. This could have an adverse effect on nutritional status.

- Loss of hearing may lead to less eating out or not asking questions of the waiter or store clerk.

- Changes in smell and taste are more obvious. If food doesn’t taste appetizing or smell appealing, we don’t want to eat it. If we must cut back on salt, sugar or fat, we may tend not to eat.

Structural Changes

As we age, we lose lean body mass. Reduced muscle mass includes skeletal muscle, smooth muscle and muscle that affects vital organ function, with loss of cardiac muscle perhaps the most important. Cardiac capacity can be reduced and cardiac function impaired by chronic diseases such as athero-sclerosis, hypertension or diabetes. Changes also occur in the kidneys, lungs and liver, and in our ability to generate new protein tissue. In addition, aging can slow the immune system’s response in making antibodies.

The most significant result of the loss of lean body mass may be the decrease in basal energy metabolism. Metabolic rate declines proportionately with the decline in total protein tissue. To avoid gaining weight, we must reduce calorie intake or increase activity. The goal is energy balance.

Loss of lean body mass also means reduced body water — 72 percent of total body water is in lean muscle tissue.

Total body fat typically increases with age. This often can be explained by too many calories. As we age, fat tends to concentrate in the trunk and as fat deposits around the vital organs. However, in more advanced years, weight often declines.

Finally, we lose bone density. After menopause, women tend to lose bone mass at an accelerated rate. Recent attention has focused on the high incidence of osteoporosis. Severe osteoporosis is debilitating and serious.

Fractures and their associated illness and mortality are certainly a concern. Also, vertebral compression fractures can change chest configuration. This, in turn, can affect breathing, intestinal distension and internal organ displacement.

Nutrition can be a factor in all of the changes noted above. However, the slowing of the normal action of the digestive tract plus general changes have the most direct effect on nutrition. Digestive secretions diminish markedly, although enzymes remain adequate. Adequate dietary fiber, as opposed to increased use of laxatives, will maintain regular bowel function and not interfere with the digestion and absorption of nutrients, as occurs with laxative use or abuse.

Suggestions for Coping with Change

Sensory changes

Loss of smell and taste affect the nutritional intake and status of many seniors. If food does not smell or taste appetizing, it will not be eaten.

Suggestions:

- Try a variety of new food flavors. Experiment with low sodium seasonings such as lemon juice, dill, curry and herbs of all types (see fact sheet 9.354, Sodium in the Diet).

- Sometimes the problem is not dulled senses, but rather a drab, soft diet. Don’t cook vegetables until they are mushy. Instead, reawaken the senses to fresh, flavorful foods and new textures

Loss of teeth

Improperly fitting dentures may unconsciously change eating patterns because of difficulty with chewing. A soft, low-fiber diet without important fresh fruits and vegetables may result.

Suggestions:

- Have poorly fitting dentures adjusted.

- Chop, steam, stew, grind or grate hard or tough foods to make them easier to chew without sacrificing their nutritional value. Try a grated carrot and raisin salad.

Osteoporosis

Weight-bearing exercise and a diet high in calcium help protect against osteoporosis. Current treatments include estrogen replacement, exercise and calcium supplements. (See 9.359, Osteoporosis.)

Suggestions:

- Walk, lift weights, swim or enroll in a group fitness or water aerobics class. Exercise at least three times a week and have fun!

- Include two to four daily servings of dairy products such as milk, yogurt or cheese.

- If digesting milk is a problem, cultured dairy products, like buttermilk and yogurt, often are tolerated well. Use lactaid, available in most stores, to make reduced lactose milk.

- Post-menopausal women may need a calcium supplement if they can’t get enough through diet alone. Talk to a physician or registered dietitian.

Specific Nutrient Needs

Calorie needs change due to more body fat and less lean muscle. Less activity can further decrease calorie needs. The challenge for the elderly is to meet the same nutrient needs as when they were younger, yet consume fewer calories.

The answer to this problem is to choose foods high in nutrients in relation to their calories. Such foods are considered “nutrient-dense.” For example, low-fat milk is more nutrient dense than regular milk. Its nutrient content is the same, but it has fewer calories because it has less fat.

Protein needs usually do not change for the elderly, although research studies are not definitive. Protein requirements can vary because of chronic disease. Balancing needs and restrictions is a challenge, particularly in health care facilities. Protein absorption may decrease as we age, and our bodies may make less protein. However, this does not mean protein intake should be routinely increased, because of the general decline in kidney function. Excess protein could unnecessarily stress kidneys.

Reducing the overall fat content in the diet is reasonable. It is the easiest way to cut calories. This is appropriate to reduce weight. Lower fat intake is often necessary because of chronic disease.

About 60 percent of calories should come from carbohydrates, with emphasis on complex carbohydrates. Glucose tolerance may decrease with advancing years. Complex carbohydrates put less stress on the circulating blood glucose than do refined carbohydrates.

Such a regime also enhances dietary fiber intake. Adequate fiber, together with adequate fluid, helps maintain normal bowel function. Fiber also is thought to decrease risk of intestinal inflammation. Vegetables, fruits, grain products, cereals, seeds, legumes and nuts are all sources of dietary fiber (See fact sheet 9.333, Dietary Fiber).

Vitamins and Minerals

Vitamin deficiencies may not be obvious in many older people. However, any illness stresses the body and may be enough to use up whatever stores there are and make the person vitamin deficient. Medications also interfere with many vitamins. When drug histories are looked at, nutrient deficiencies emerge. Eating nutrient-dense foods becomes increasingly important when calorie needs decline but vitamin and mineral needs remain high.

The body can store fat-soluble vitamins and usually the elderly are at lower risk of fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies. Always provide vitamin D-fortified milk for the housebound, nursing home residents, and anyone who does not get adequate exposure to sunlight.

Iron and calcium intake sometimes appears to be low in many elderly. To improve absorption of iron, include vitamin C-rich fruits and vegetables with these foods (See 9,356, Iron: An Essential Nutrient). For example, have juice or sliced fruit with cereal, a baked potato with roast beef, vegetables with fish, or fruit with chicken. To boost your intake of calcium, have tomato slices in a cheese sandwich, or salsa with a bean burrito.

Zinc can be related to specific diseases in the elderly. It can also be a factor with vitamin K in wound healing. Zinc improves taste acuity in people where stores are low. Habitual use of more than 15 mg per day of zinc supplements, in addition to dietary intake, is not recommended without medical supervision. If you eat meats, eggs and seafood, zinc intake should be adequate. This underscores the importance of eating a wide variety of foods.

Zinc along with vitamins C and E, and the phytochemicals lutein, zeaxanthin and beta-carotene may help prevent or slow the onset of age-related macular degeneration. The best way to obtain these nutrients is to consume at least five servings of fruits and vegetables, especially dark green, orange and yellow ones. Good choices include kale, spinach, broccoli, peas, oranges and cantaloupes. Consult your doctor to see if a supplement may also be necessary.

Vitamin E may have a potential role in the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Research has shown that eating foods with vitamin E, like whole grains, peanuts, nuts, vegetable oils, and seeds, may help reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. However, the same benefits did not hold true for vitamin E from supplements.

Low levels of vitamin B12 have been associated with memory loss and linked to age-related hearing loss in older adults. Folate, which is related to B12 metabolism in the body, may actually improve hearing. However, if B12 levels are not adequate, high folate levels may be a health concern. As we age, the amount of the chemical in the body, needed to absorb vitamin B12 decreases. To avoid deficiency, older adults are advised to eat foods rich in vitamin B12 regularly, including meat, poultry, fish, eggs and dairy foods. Consult your doctor to see if a vitamin B12 supplement may also be necessary.

Drugs used to control diseases such as hypertension or heart disease can alter the need for electrolytes, sodium and potassium. (See 9.361, Nutrient-Drug Interactions and Food.) Even though absorption and utilization of some vitamins and minerals becomes less effective with age, higher intakes do not appear to be necessary. As for any age group, it’s important to enjoy a wide variety of foods. Also, if you are taking an herbal or dietary supplement, make sure to tell your doctor, since these supplements may interact with other drugs or nutrients in your diet.

Water

Generally, water as a nutrient receives little attention once a person is old enough to talk. However, of all the nutrients, water is the most important, serving many essential functions.

Adequate water intake reduces stress on kidney function, which tends to decline with age. Adequate fluid intake also eases constipation. With the aging process, the ability to detect thirst declines, so do not wait to drink water until you are thirsty. Drink plenty of water, juice, milk, and coffee or tea to stay hydrated. Drink the equivalent to five to eight glasses everyday. It may be helpful to use a cup or water bottle which has calibrated measurements on it, in order to keep track of how much you drink. Carry it with you throughout your home or wherever you go during the day.

Variety of Foods

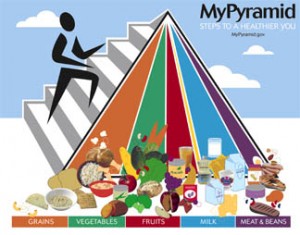

Figure 1: Go to the Web site www.MyPyramid.gov to find your personalized pyramid for good health. |

People of all ages need more than 40 nutrients to stay healthy. With age, it becomes more important that diets contain enough calcium, fiber, iron, protein, and the vitamins A, C, D and Folacin. Reduce calories, select nutrient-dense foods, and enjoy smaller portions of foods high in fat, sugar and sodium. Because no one food or pill provides all of the nutrients, eat a variety of foods to get the full spectrum of nutrients.

Variety often is lacking in the diets of seniors, who often eat the same foods over and over again. Get out of this food rut by trying some of these suggestions:

- Eat breakfast foods for lunch or lunch foods for dinner.

- Use color as a guide for variety in a meal. A good meal should provide three distinct colors on the plate.

- Increase the variety of texture in meals. Add whole grain breads (rye, wheat, pumpernickel), whole grain cereals, and cooked legumes (beans of all types, lentils, dried peas).

- Eat at least five servings of fruits and vegetables each day.

- Build your diet as MyPyramid recommends. (See Figure 1.)

Eating Alone

Pamper yourself and pay special attention to meal preparation. If eating alone means skipping meals or not eating a variety of foods, try one of the following to add mealtime sparkle: (See fact sheet 9.351, Meals for 1 or 2)

- Start an eating club.

- Eat by a window and use the best dishes.

- Eat a lunch in the park.

- Treat yourself to a meal out.

- Invite a friend to a potluck dinner.

- Attend the nutrition program for the elderly and enjoy meals in the community.

- During an illness, arrange for home-delivered meals from the community nutrition program for the elderly.

- Make leftovers into “planned leftovers.”

- Prepare a new recipe each week and invite friends over for a tasting party.

- Use frozen prepared dinners for added variety and convenience.

- Add a special touch to your table, like a colorful table cloth or placemats, a plant, candle, or decorative vase.

Buy More Nutrients Per Food Dollar

On any budget, it requires planning to buy a variety of nutrient-rich foods. You get more nutrients for your dollar from milk, eggs, legumes, grain, lean meat, fish or poultry than from prepared processed foods, ready-made desserts and snack foods.

- Look for specials. Check the newspaper ads for sales on meat, fish, poultry, fruits and vegetables.

- Use coupons. Coupons save money on products you usually buy. Buying expensive convenience foods with coupons may cost more.

- Plan ahead. Buy an advertised meat special to use for several meals. Freeze portions for later use. Keep a supply of food on hand for bad weather or illness. Also, buy a few gallons of water to keep on hand in case of an emergency.

- Make a shopping list. Plan meals for the week, then make a list of the food needed.

- Shopping. Shop when the store is not crowded and after a meal. Ask for help at the store, if needed, or shop with a friend.

- Shop on the telephone. Many stores will deliver your order if you are unable to go to the store. Check what is available in your community.

- Read the labels. Find out the ingredients in the food and its expiration date. If you can’t find the date, ask for the information. If enough people ask, it will appear in larger print.

- Read the nutrition labels. When the label says “low calorie” or “low sodium,” check the nutrition information label for the number of calories and amount of sodium per serving. Sodium labels give valuable information on the sodium content per serving: sodium free, 5 mg; very low sodium, 35 mg; low sodium, 140 mg; reduced sodium, 75 percent less sodium than before. Unsalted foods or foods processed without salt may still contain sodium. If necessary take a magnifying glass to read the fine print on the labels.

- Use unit pricing. Unit pricing helps you find the best buy. The unit pricing label tells the cost per unit of measure such as ounce, serving or pound. Use this to compare brands and different size packages to get the most food per dollar.

References

- Eating For Your Health. American Association of Retired Persons, l909 K Street, NW, Washington, D.C., 20049.

- Duyff, Roberta Larson. American Dietetic Association’s Complete Food and Nutrition Guide, 2nd edition. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. 2002.

- Anderson, J. and K. Petre. Nutrition Which Promotes Health and Wellness. Mary Scott Lecture Series Proceedings. April, 1988.

- Metress, S. and C. Kart. Nutrition, the Aged and Society. Prentice Hall Publ. Co.

- Meydani, S.N., Wekslev, M.E. Nutrition, Aging and Immune Function. Nutrition Reviews 53:4, April 1995.

- Roe, Daphne. Geriatric Nutrition. Prentice Hall Publ. Co.

- Tufts University Health and Nutrition Letter. April 2007.

- UC Berkley Wellness Letter, April 2007.

- Young at Heart, Tips for Older Adults.http://win.niddk.nih.gov/publications/young_heart.htm.

1 J.E. Anderson, Colorado State University Extension foods and nutrition specialist and professor, food science and human nutrition; and S. Prior former graduate intern, food science and human nutrition. 12/98. Reviewed 4/07.

Colorado State University, U.S. Department of Agriculture and Colorado counties cooperating. CSU Extension programs are available to all without discrimination. No endorsement of products mentioned is intended nor is criticism implied of products not mentioned.